Also check out: Listen Little Man

Excerpts from

The Mass Psychology of Fascism

Also check out: Listen Little Man

Excerpts from

The Mass Psychology of Fascism

The German freedom movement prior to Hitler was inspired by Karl Marx's economic and social theory. Hence, an understanding of German fascism must proceed from an understanding of Marxism.

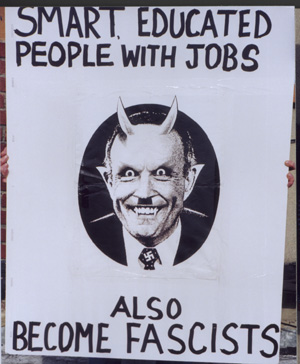

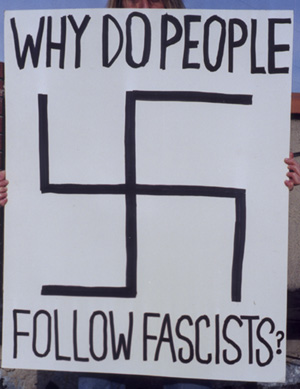

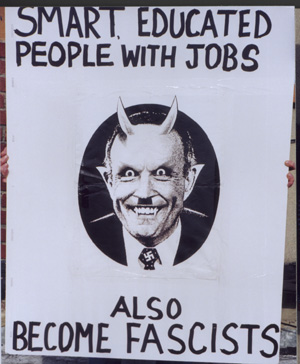

In the months following National Socialism's seizure of power in Germany, even those individuals whose revolutionary firmness and readiness to be of service had been proven again and again, expressed doubts about the correctness of Marx's basic conception of social processes. These doubts were generated by a fact that, though irrefutable, was at first incomprehensible: Fascism, the most extreme representative of political and economic reaction in both its goals and its nature, had become an international reality and in many countries had visibly and undeniably outstripped the socialist revolutionary movement. That this reality found its strongest expression in the highly industrialized countries only heightened the problem. The rise of nationalism in all parts of the world offset the failure of the workers' movement in a phase of modern history in which, as the Marxists contended, "the capitalist mode of production had become economically ripe for explosion." Added to this was the deeply ingrained remembrance of the failure of the Workers' International at the outbreak of World War I and of the crushing of the revolutionary uprisings outside of Russia between 1918 and 1923. They were doubts, in short, which were generated by grave facts if they were justified, then the basic Marxist conception was false and the workers' movement was in need of a decisive reorientation, provided one still wanted to achieve its goals. If, however, the doubts were not justified, and Marx's basic conception of sociology was correct, then not only was a thorough and extensive analysis of the reasons for the continual failure of the workers' movement called for, but also and this above all-a complete elucidation of the unprecedented mass movement of fascism was also needed. Only from this could a new revolutionary practice result.

A change in the situation was out of the question unless it could be proven that either the one or the other was the case. It was clear that neither an appeal to the "revolutionary class consciousness" of the working class nor the practice á la Coué -the camouflaging of defeats and the covering of important facts with illusions-a practice that was in vogue at that time, could lead to the goal. One could not content oneself with the fact that the workers' movement was also 'progressing," that here and there resistance was being offered and strikes were being called. What is decisive is not that progress is being made, but at what tempo, in relation to the international strengthening and advance of political reaction.

The young work-democratic, sex-economic movement is interested in a thorough clarification of this question not only because it is a part of the social liberation fight in general but chiefly because the achievement of its goals is inextricably related to the achievement of the political and economic goals of natural work-democracy. For this reason we want to try to explain how the specific sex-economic questions are interlaced with the general social questions, seen from the perspective of the workers' movement.

In some of the German meetings around 1930 there were intelligent, straightforward, though nationalistically and mystically oriented, revolutionaries-such as Otto Strasser, for example-who were wont to confront the Marxists as follows: "You Marxists like to quote Marx's theories in your defense. Marx taught that theory is verified by practice only, but your Marxism has proved to be a failure. You always come around with explanations for the defeat of the Workers' International. The 'defection of the Social Democrats' was your explanation for the defeat of

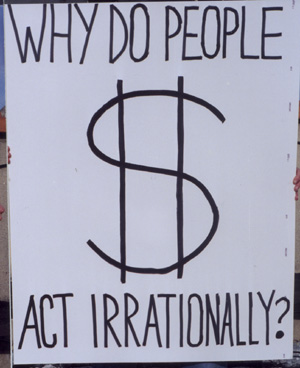

1914; you point to their 'treacherous politics' and their illusions to account for the defeat of 1918. And again you have ready 'explanations' to account for the fact that in the present world crisis the masses are turning to the Right instead of to the Left. But your explanations do not blot out the fact of your defeats! Eighty years have passed, and where is the concrete confirmation of the theory of social revolution? Your basic error is that you reject or ridicule soul and mind and that you don't comprehend that which moves everything." Such were their arguments, and exponents of Marxism had no answer. It became more and more clear that their political mass propaganda, dealing as it did solely with the discussion of objective socio-economic processes at a time of crisis (capitalist modes of production, economic anarchy, etc.), did not appeal to anyone other than the minority already enrolled in the Left front. The playing up of material needs and of hunger was not enough, for every political party did that much, even the church; so that in the end it was the mysticism of the National Socialists that triumphed over the economic theory of socialism, and at a time when the economic crisis and misery were at their worst. Hence, one had to admit that there was a glaring omission in the propaganda and in the overall conception of socialism and that, moreover, this omission was the source of its "political errors." It was an error in the Marxian comprehension of political reality, and yet all the prerequisites for its correction were contained in the methods of dialectical materialism. They had simply never been turned to use. In their political practice, to state it briefly at the outset, the Marxists had failed to take into account the character structure of the masses and the social effect of mysticism.

Those who followed, and were practically involved in the revolutionary Left's application of Marxism between 1917 and 1933, had to notice that it was restricted to the sphere of objective economic processes and governmental policies, but that it neither kept a close eye on nor comprehended the development and contradictions of the so-called "subjective factor" of history, i.e., the ideology of the masses. The revolutionary Left failed, above all, to make fresh use of its own method of dialectical materialism, to keep it alive, to comprehend every new social reality from a new perspective with this method.

The use of dialectical materialism to comprehend new historical realities was not cultivated, and fascism was a reality that neither Marx nor Engels was familiar with, and was caught sight of by Lenin only in its beginnings. The reactionary conception of reality shuts its eyes to fascism's contradictions and actual conditions. Reactionary politics automatically makes use of those social forces that oppose progress; it can do this successfully only as long as science neglects to unearth those revolutionary forces that must of necessity overpower the reactionary forces. As we shall see later, not only regressive but also very energetic progressive social forces emerged in the rebelliousness of the lower middle classes, which later constituted the mass basis of fascism. This contradiction was overlooked; indeed, the role of the lower middle classes was altogether in eclipse until shortly before Hitler's seizure of power.

Revolutionary activity in every area of human existence will come about by itself when the contradictions in every new process are comprehended; it will consist of an identification with those forces that are moving in the direction of genuine progress. To be radical, according to Karl Marx, means "getting to the root of things." If one gets to the root of things, if one grasps their contradictory operations, then the overcoming of political reaction is assured. If one does not get to the root of things, one ends, whether one wants to or not, in mechanism, in economics, or even in metaphysics, and inevitably loses one's footing. Hence, a critique can only be significant and have a practical value if it can show where the contradictions of social reality were overlooked. What was revolutionary about Marx was not that he wrote this or that proclamation or pointed out 9 revolutionary goals; his major revolutionary contribution is that he recognized the industrial productive forces as the progressive force of society and that he depicted the contradictions of capitalist economy as they relate to real life. The failure of the workers' movement must mean that our knowledge of those forces that retard social progress is very limited, indeed, that some major factors are still altogether unknown.

As so many works of great thinkers, Marxism also degenerated to hollow formulas and lost its scientific revolutionary potency in the hands of Marxist politicians. They were so entangled in everyday political struggles that they failed to develop the principles of a vital philosophy of life handed down by Marx and Engels. To confirm this, one need merely compare Sauerland's book on "Dialectical Materialism" or any of Salkind's or Pieck's books with Marx's Das Kapital or Engels' The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science. Flexible methods were reduced to formulas; scientific empiricism to rigid orthodoxy. In the meantime the "proletariat" of Marx's time had developed into an enormous class of industrial workers, and the middle-class shopkeepers had become a colossus of industrial and public employees. Scientific Marxism degenerated to "vulgar Marxism." This is the name many outstanding Marxist politicians have given to the economics that restricts all of human existence to the problem of unemployment and pay rates.

It was this very vulgar Marxism that maintained that the economic crisis of 1929-33 was of such a magnitude that it would of necessity lead to an ideological Leftist orientation among the stricken masses. While there was still talk of a "revolutionary revival" in Germany, even after the defeat of January 1933, the reality of the situation showed that the economic crisis, which, according to expectations, was supposed to entail a development to the Left in the ideology of the masses, had led to an extreme development to the Right in the ideology of the proletarian strata of the population. The result was a cleavage between the economic basis, which developed to the Left, and the ideology of broad layers of society, which developed to the Right. This cleavage was overlooked; consequently, no one gave a thought to asking how broad masses living in utter poverty could become nationalistic. Explanations such as "chauvinism," "psychosis," "the consequences of Versailles," are not of much use, for they do not enable us to cope with the tendency of a distressed middle class to become radical Rightist; such explanations do not really comprehend the processes at work in this tendency. In fact, it was not only the middle class that turned to the Right, but broad and not always the worst elements of the proletariat. One failed to see that the middle classes, put on their guard by the success of the Russian Revolution, resorted to new and seemingly strange preventative measures (such as Roosevelt's "New Deal"), which were not understood at that time and which the workers' movement neglected to analyze. One also failed to see that, at the outset and during the initial stages of its development to a mass movement, fascism was directed against the upper middle class and hence could not be disposed of "merely as a bulwark of big finance," if only because it was a mass movement.

Where was the problem?

The basic Marxist conception grasped the facts that labor was exploited as a commodity, that capital was concentrated in the hands of the few, and that the latter entailed the progressive pauperization of the majority of working humanity. It was from this process that Marx arrived at the necessity of "expropriating the expropriators." According to this conception, the forces of production of capitalist society transcend the limits of the modes of production. The contradiction between social production and private appropriation of the products by capital can only be cleared up by the balancing of the modes of production with the level of the forces of production. Social production must be complemented by the social appropriation of the products. The first act of this assimilation is social revolution; this is the basic economic principle of Marxism. This assimilation can take place, it is said, only if the pauperized majority establishes the "dictatorship of the proletariat" as the dictatorship of the working majority over the minority of the now expropriated owners of the means of production.

According to Marx's theory the economic preconditions for a social revolution were given: capital was concentrated in the hands of the few, the growth of national economy to a world economy was completely at variance with the custom and tariff system of the national states; capitalist economy had achieved hardly half of its production capacity, and there could no longer be any doubt about its basic anarchy. The majority of the population of the highly industrialized countries was living in misery; some fifty million people were unemployed in Europe; hundreds of millions of workers scraped along on next to nothing. But the expropriation of the expropriators failed to take place and, contrary to expectations, at the crossroads between "socialism and barbarism," it was in the direction of barbarism that society first proceeded. For the international strengthening of fascism and the lagging behind of the workers' movement was nothing other than that. Those who still hoped for a revolution to result from the anticipated second World War, which in the meantime had become a reality -those, in other words, who counted on the masses to turn the weapons thrust into their hands against the inner enemy-had not followed the development of the new techniques of war. One could not simply reject the reasoning to the effect that the arming of the broad masses would be highly unlikely in the next war. According to this conception, the fighting would be directed against the unarmed masses of the large industrial centers and would be carried out by very reliable and selected war-technicians. Hence, a reorientation of one's thinking and one's evaluations was the precondition of a new revolutionary practice. World War II was a confirmation of these expectations.

ECONOMIC AND IDEOLOGICAL STRUCTURE OF THE GERMAN SOCIETY, 1928~1933

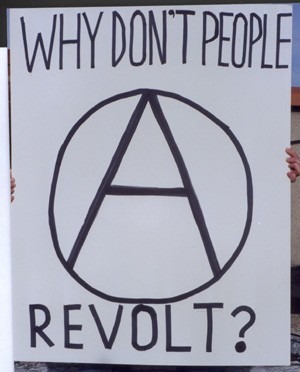

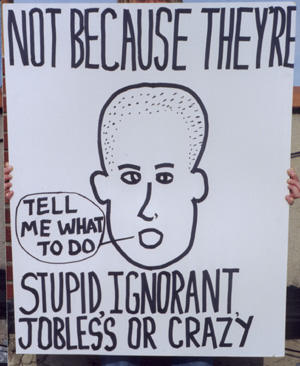

Rationally considered, one would expect economically wretched masses of workers to develop a keen consciousness of their social situation; one would further expect this consciousness to harden into a determination to rid themselves of their social misery. In short, one would expect the socially wretched working man to revolt against the abuses to which he is subjected and to say: "After all, I perform responsible social work. It is upon me and those like me -that the weal and ill of society rests. I myself assume the responsibility for the work that must be done." In such a case, the thinking ("consciousness") of the worker would be in keeping with his social situation. The Marxist called it "class consciousness." We want to call it "consciousness of one's skills," or "consciousness of one's social responsibility." The cleavage between the social situation of the working masses and their consciousness of this situation implies that, instead of improving their social position, the working masses worsen it. It was precisely the wretched masses who helped to put fascism, extreme political reaction, into power.

It is a question of the role of ideology and the emotional attitude of these masses seen as a historical factor, a question of the repercussion of the ideology on the economic basis. If the material wretchedness of the broad masses did not lead to a social revolution; if, objectively considered, contrary revolutionary ideologies resulted from the crisis, then the development of the ideology of the masses in the critical years thwarted the "efflorescence of the forces of production," prevented, to use Marxist concepts, the "revolutionary resolution of the contradictions between the forces of production of monopolistic capitalism and its methods of production."

No matter how many middle-class employees may have voted for left-wing parties and how many workers may have voted for right-wing parties, it is nonetheless striking that the figures of the ideological distribution, arrived at by us, agree approximately with the election figures of 1932: Taken together the Communists and the Social Democrats received twelve to thirteen million votes, while the NSDAP* (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) and the German Nationalists received some nineteen to ~ twenty million votes. Thus, with respect to practical politics, it was not the economic but the ideological distribution that was decisive. In short, the political importance of the lower middle class is greater than had been assumed.

During the rapid decline of the German economy, 1929-32, the NSDAP jumped from 800,000 votes in 1928 to 6,400,000 in the fall of 1930, to 13,000,000 in the summer of 1932 and 17,000,000 in January of 1933. According to Jager's calculations ("Hitler," Roter Aulbau, October 1930) the votes cast by the workers made up approximately 3,000,000 of the 6,400,000 votes received by the National Socialists in 1930. Of these 3,000,000 votes, some 60 to 70 percent came from employees and 30 to 40 percent from workers.

To my knowledge it was Karl Radek who most dearly grasped the problematic aspect of this sociological process as early as 1930, following the NSDAP's first upsurge. He wrote

"Nothing similar to this is known in the history of political struggle, particularly in a country with firmly established political differentiations, in which every new party has had to fight for any position held by the old parties. There is nothing more characteristic than the fact that, neither in bourgeois nor in socialist literature, has anything been said about this party, which assumes the second place in German political life. It is a party without history which suddenly emerges in German political life, just as an island suddenly emerges in the middle of the sea owing to volcanic forces.

-"German Elections," Roter Aufbau, October, 1930

We have no doubt that this island also has a history and follows an inner logic.

The choice between the Marxist alternative: "fall to barbarism" or "rise to socialism," was a choice that, according to all previous experience, would be determined by the ideological structure of the dominated classes. Either this structure would be in keeping with the economic situation or it would be at variance with it, as, for instance, we find in large Asian societies, where exploitation is passively endured, or in present-day Germany, where a cleavage exists between economic situation and ideology.

Thus, the basic problem is this: What causes this cleavage, or to put it another way, what prevents the economic situation from coinciding with the psychic structure of the masses? It is a problem, in short, of comprehending the nature of the psychological structure of the masses and its relation to the economic basis from which it derives.

To comprehend this, we must first of all free ourselves from vulgar Marxist concepts, which only block the way to an understanding of fascism. Essentially, they are as follows:

In accordance with one of its formulas, vulgar Marxism completely separates economic existence from social existence as a whole, and states that man's "ideology" and "consciousness" are solely and directly determined by his economic existence. Thus, it sets up a mechanical antithesis between economy and ideology, between "structure" and "superstructure"; it makes ideology rigidly and one-sidedly dependent upon economy, and fails to see the dependency of economic development upon that of ideology. For this reason the problem of the so-called "repercussion of ideology" does not exist for it. Notwithstanding the fact that vulgar Marxism now speaks of the "lagging behind of the subjective factor," as Lenin understood it, it can do nothing about it in a practical way, for its former conception of ideology as the product of the economic situation was too rigid. It did not explore the contradictions of economy in ideology, and it did not comprehend ideology as a historical force.

In fact, it does everything in its power not to comprehend the structure and dynamics of ideology; it brushes it aside as "psychology," which is not supposed to be "Marxistic," and leaves the handling of the subjective factor, the so-called "psychic life" in history, to the metaphysical idealism of political reaction, to the Gentiles and Rosenbergs, who make "mind" and "soul" solely responsible for the progress of history and, strange to say, have enormous success with this thesis. The neglect of this aspect of sociology is something Marx himself criticized in the materialism of the eighteenth century. To the vulgar Marxist, psychology is a metaphysical system pure and simple, and he draws no distinction whatever between the metaphysical character of reactionary psychology and the basic elements of psychology, which were furnished by revolutionary psychological research and which it is our task to develop. The vulgar Marxist simply negates, instead of offering constructive criticism, and feels himself to be a "materialist" when he rejects facts such as "drive," "need," or "inner process," as being "idealistic." The result is that he gets into serious difficulties and meets with one failure after another, for he is continually forced to employ practical psychology in political practice, is forced to speak of the "needs of the masses," "revolutionary consciousness," "the will to strike," etc. The more the vulgar Marxist tries to gainsay psychology, the more he finds himself practicing metaphysical psychologism and worse, insipid Coueism. For example, he will try to explain a historical situation on the basis of a "Hitler psychosis," or console the masses and persuade them not to lose faith in Marxism. Despite everything, he asserts, headway is being made, the revolution will not be subdued, etc. He sinks to the point finally of pumping illusionary courage into the people, without in reality saying anything essential about the situation, without having comprehended what has happened. That political reaction is never at a loss to find a way out of a difficult situation, that an acute economic crisis can lead to barbarism as well as it can lead to social freedom, must remain for him a book with seven seals. Instead of allowing his thoughts and acts to issue from social reality, he transposes reality in his fantasy in such a way as to make it correspond to his wishes.

Our political psychology can be nothing other than an investigation of this "subjective factor of history," of the character structure of man in a given epoch and of the ideological structure of society that it forms. Unlike reactionary psychology and psychologistic economy, it does not try to lord it over Marxist sociology by throwing "psychological conceptions" of social processes in its teeth, but gives it its proper due as that which deduces consciousness from existence.

The Marxist thesis to the effect that originally "that which is materialistic" (existence) is converted into "that which is ideological" (in consciousness), and not vice versa, leaves two questions open: (1) how this takes place, what happens in man's brain in this process; and (2) how the "consciousness" (we will refer to it as psychic structure from now on) that is formed in this way reacts upon the economic process. Character-analytic psychology fills this gap by revealing the process in man's psychic life, which is determined by the conditions of existence. By so doing, it puts its finger on the "subjective factor," which the vulgar Marxist had failed to comprehend. Hence, political psychology has a sharply delineated task. It cannot, for instance, explain the genesis of class society or the capitalist mode of production (whenever it attempts this, the result is always reactionary nonsense-for instance, that capitalism is a system of man's greed). Nonetheless, it is political psychology-and not social economy-that is in a position to investigate the structure of man's character in a given epoch, to investigate how he thinks and acts, how the contradictions of his existence work themselves out, how he tries to cope with his existence, etc. To be sure, it examines individual men and women only. If, however, it specializes in the investigation of typical psychic processes common to one category, class, professional group, etc., and excludes individual differences, then it becomes a mass psychology. Thus it proceeds directly from Marx himself.

"The presuppositions with which we begin are not arbitrary presuppositions; they are not dogmas; they are real presuppositions from which one can abstract only in fancy. They are the actual individuals, their actions and the material conditions of their lives, those already existing as well as those produced by action."

-German Ideology

"Man himself is the basis of his material production, as of every other production which he achieves. In other words all conditions affect and more or less modify all of the functions and activities of man-the subject of production & the creator of material wealth, of commodities. In this connection it can be indeed proven that all human conditions and functions, no matter how and when they are manifested, influence material production and have a more or less determining effect on them."

-Theory of Surplus Value

Hence, we are not saying anything new, and we are not revising Marx, as is so often maintained: "All human conditions," that is, not only the conditions that are a part of the work process, but also the most private and most personal and highest accomplishments of human instinct and thought; also, in other words, the sexual life of women and adolescents and children, the level of the sociological investigation of these conditions and its application to new social questions. With a certain kind of these "human conditions," Hitler was able to bring about a historical situation that is not to be ridiculed out of existence. Marx was not able to develop a sociology of sex, because at that time sexology did not exist. Hence, it now becomes a question of incorporating both the purely economic and sex-economic conditions into the framework of sociology, of destroying the hegemony of the mystics and metaphysicians in this domain.

When an "ideology has a repercussive effect upon the economic process," this means that it must have become a material force. When an ideology becomes a material force, as soon as it has the ability to arouse masses, then we must go on to ask: How does this take place? How is it possible for an ideologic factor to produce a materialistic result, that for a theory to produce a revolutionary effect? The answer to this question must also be the answer to the question of reactionary mass psychology; it must, in other words, elucidate the "Hitler psychosis."

The ideology of every social formation has the function not only of reflecting the economic process of this society, but also and more significantly of embedding this economic process in the psychic structures of the people who make up the society. Man is subject to the conditions of his existence in a twofold way: directly through the immediate influence of his economic and social position, and indirectly by means of the ideologic structure of the society. His psychic structure, in other words, is forced to develop a contradiction corresponding to the contradiction between the influence exercised by his material position and the influence exercised by the ideological structure of society. The worker, for instance, is subject to the situation of his work as well as to the general ideology of the society. Since man however, regardless of class, is not only the object of these influences but also reproduces them in his activities, his thinking and acting must be just as contradictory as the society from which they derive. But, inasmuch as a social ideology changes man's psychic structure, it has not only reproduced itself in man but, what is more significant, has become an active force, a material power in man, who in turn has become concretely changed, and, as a consequence thereof, acts in a different and contradictory fashion. It is in this way and only in this way that the repercussions of a society's ideology on the economic basis from which it derives is possible. The "repercussion" loses its apparent metaphysical and psychologistic character when it can be comprehended as the functioning of the character structure of socially active man. As such, it is the object of natural scientific investigations of the character. Thus, the statement that the "ideology" changes at a slower pace than the economic basis is invested with a definite cogency. The basic traits of the character structures corresponding to a definite historical situation are formed in early childhood, and are far more conservative than the forces of technical production. It results from this that, as time goes on, the psychic structures lag behind the rapid changes of the social conditions from which they derived, and later come into conflict with new forms of life. This is the basic trait of the nature of so-called tradition, i.e., of the contradiction between the old and the new social situation.

HOW MASS PSYCHOLOGY SEES THE PROBLEM

We begin to see now that the economic and ideologic situations of the masses need not necessarily coincide, and that, indeed, there can be a considerable cleavage between the two The economic situation is not directly and immediately converted into political consciousness. If this were the case, the social revolution would have been here long ago. In keeping with this dichotomy of social condition and social consciousness, the investigation of society must proceed along two different lines. Notwithstanding the fact that the basic structure derives from the economic existence, the economic situation has to be comprehended with methods other than those used to comprehend the character structure: the former has to be comprehended socio-economically, the latter biopsychologically. Let us illustrate this with a simple example. When workers who are hungry, owing to wage-squeezing, go on strike, their act is a direct result of their economic situation. The same applies to the man who steals food because he is hungry. That a man steals because he is hungry, or that workers strike because they are being exploited, needs no further psychological clarification. In both cases ideology and action are commensurate with economic pressure. Economic situation and ideology coincide with one another. Reactionary psychology is wont to explain the theft and the strike in terms of supposed irrational motives; reactionary rationalizations are invariably the result. Social psychology sees the problem in an entirely different light: what has to be explained is not the fact that the man who is hungry steals or the fact that the man who is exploited strikes, but why the majority of those who are hungry don't steal and why the majority of those who are exploited don't strike. Thus, social economy can give a complete explanation of a social fact that serves a rational end, i.e., when it satisfies an immediate need and reflects and magnifies the economic situation. The social economic explanation does not hold up, on the other hand, when a man's thought and action are inconsistent with the economic situation, are irrational, in other words. The vulgar Marxist and the narrow-minded economist, who do not acknowledge psychology, are helpless in the face of such a contradiction. The more mechanistically and economistically oriented a sociologist is, the less he knows about man's psychic structure, the more he is apt to fall prey to superficial psychologism in the practice of mass propaganda. Instead of probing and resolving the psychic contradictions in the individuals of the masses, he has recourse to insipid Coueism or he explains the nationalistic movement on the basis of a "mass psychosis." (In view of the fact that the economist neither knows nor acknowledges the existence of psychic processes, the words "mass psychosis." do not mean to him what they mean to us namely a social circumstance of enormous historical importance, to him it is a matter of no social significance whatever.) Hence, the line of questioning of mass psychology begins precisely at the point where the immediate socio-economic explanation hits wide of the mark. Does this mean that mass psychology and social economy serve cross purposes? No. For thinking and acting on the part of the masses contradictory to the immediate socio-economic situation, i.e., irrational thinking and acting, are themselves the result of an earlier, older socio-economic situation. One is wont to explain the repression of social consciousness by so-called tradition. But no investigation has been made as yet to determine just what "tradition" is, to determine which psychic elements are molded by it. Narrow-minded economy has repeatedly failed to see that the most essential question does not relate to the workers' consciousness of social responsibility (this is self-evident) but to what it is that inhibits the development of this consciousness of responsibility.

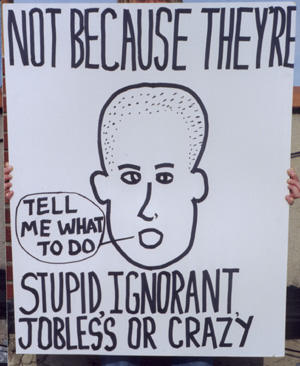

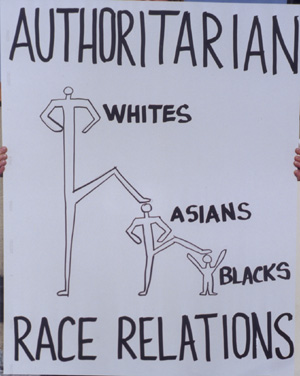

Ignorance of the character structure of masses of people invariably leads to fruitless questioning. The Communists, for example, said that it was the misdirected policies of the Social Democrats that made it possible for the fascists to seize power. Actually this explanation did not explain anything, for it was precisely the Social Democrats who made a point of spreading illusions. In short, it did not result in a new mode of action. That political reaction in the form of fascism had "befogged," "corrupted," and "hypnotized" the masses is an explanation that is as sterile as the others. This is and will continue to be the function of fascism as long as it exists. Such explanations are sterile because they fail to offer a way out. Experience teaches us that such disclosures, no matter how often they are repeated, do not convince the masses; that, in other words, social economic inquiry by itself is not enough. Wouldn't it be closer to the mark to ask what was going on in the masses that they could not and would not recognize the function of fascism? To say that "The workers have to realize . . ." or "We didn't understand . . ." does not serve any purpose. Why didn't the workers- realize, and why didn't they understand? The questions that formed the basis of discussion between the Right and the Left in the workers' movements are also to be regarded as sterile. The Right contended that the workers were not predisposed to fight; the Left, on the other hand, refuted this and asserted that the workers were revolutionary and that the Right's statement was a betrayal of revolutionary thinking. Both assertions, because they failed to see the complexities of the issue, were rigidly mechanistic. A realistic appraisal would have had to point out that the average worker bears a contradiction in himself; that he, in other words, is neither a clear-cut revolutionary nor a clear-cut conservative, but stands divided. His psychic structure derives on the one hand from the social situation (which prepares the ground for revolutionary attitudes) and on the other hand from the entire atmosphere of authoritarian society-the two being at odds with one another.

It is of decisive importance to recognize such a contradiction and to learn precisely how that which is reactionary and that which is progressive-revolutionary in the workers are set off against one another. Naturally, the same applies to the middle-class man. That he rebels against the "system" in a crisis is readily understandable. However, notwithstanding the fact that he is already in an economically wretched position, the fact that he fears progress and becomes extremely reactionary is not to be readily understood from a socio-economic point of view. In short, he too bears a contradiction in himself between rebellious feelings and reactionary aims and contents.

We do not, for instance, give a full sociological explanation of a war when we analyze the specific economic and political factors that are its immediate cause. In other words, it is only part of the story that the German annexation ambitions prior to 1914 were focused on the ore mines of Briey and Longy, on the Belgian industrial center, on the extension of Germany's colonial possessions in the Near East; or that Hitler's imperial interests were focused on the oil wells of Baku, on the factories of Czechoslovakia, etc. To be sure, the economic interests of German imperialism were the immediate decisive factors, but we also have to put into proper perspective the mass psychological basis of world wars; we have to ask how the psychological structure of the masses was capable of absorbing the imperialistic ideology, to translate the imperialistic slogans into deeds that were diametrically opposed to the peaceful, politically disinterested attitude of the German population. To say that this was due to the "defection of the leaders of the Second International" is insufficient. Why did the myriad masses of the freedom-loving and anti-imperialistic oriented workers allow themselves to be betrayed? The fear of the~ consequences involved in conscientious objection accounts only for a minority of cases. Those who went through the mobilization of 1914 know that various moods were evident among the working masses. They ranged from a conscious refusal on the part of a minority to a strange resignedness to fate (or plain apathy) on the part of very broad layers of the population, to the point of clear martial enthusiasm, not only in the middle classes but among large segments of industrial workers also. The apathy of some as well as the enthusiasm of others was undoubtedly part of the foundations of war in the structure of the masses. This function on the part of the psychology of the masses in both world wars can be understood only from the sexeconomic point of view, namely that the imperialistic ideology concretely changed the structures of the working masses to suit imperialism. To say that social catastrophes are caused by "war psychoses" or by "mass befogging" is merely to throw out phrases. Such explanations explain nothing. Besides it would be a very low estimation of the masses to suppose that they would be accessible to more befogging. The point is that every social order produces in the masses of its members that structure which it needs to achieve its main aims. ("In every epoch the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas, i.e., the class which is the ruling material power of the society also constitutes that society's ideological power. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal also has the means of ideological 'production' at its disposal, so that those who lack the means of ideological production are thereby on the average subject to those who have. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the idealistic expression of the ruling material conditions, that is to say, the ruling material conditions expressed as ideas; the conditions which enabled the one class to become the ruling class or, to put it another way, the ideas of their rulership." [Marx]) No war would be possible without this psychological structure of the masses. An essential relation exists between the economic structure of society and the mass psychological structure of its members, not only in the sense that the ruling ideology is the ideology of the ruling class, but, what is even more important for the solving of practical questions of polities, the contradictions of the economic structure of a society are also embedded in the psychological structure of the subjugated masses. Otherwise it would be inconceivable that the economic laws of a society could succeed in achieving concrete results solely through the activities of the masses subjected to them.

To be sure, the freedom movements of Germany knew of the so-called "subjective factor of history" (contrary to mechanistic materialism, Marx conceived of man as the subject of history, and it was precisely this side of Marxism that Lenin built upon); what was lacking was a comprehension of irrational, seemingly purposeless actions or, to put it another way, of the cleavage between economy and ideology. We have to be able to explain how it was possible for mysticism to have triumphed over scientific sociology. This task can be accomplished only if our line of questioning is such that a new mode of action results spontaneously from our explanation. If the working man is neither a clear-cut reactionary nor a clear-cut revolutionary, but is caught in a contradiction between reactionary and revolutionary tendencies, then if we succeed in putting our finger on this contradiction, the result must be a mode of action that offsets the conservative psychic forces with revolutionary forces. Every form of mysticism is reactionary, and the reactionary man is mystical. To ridicule mysticism, to try to pass it off as "befogging" or as "psychosis," does not lead to a program against mysticism. If mysticism is correctly comprehended, however, an antidote must of necessity result. But to accomplish this task, the relations between social situation and structural formation, especially the irrational ideas that are not to be explained on a purely socio-eeonomic basis, have to be comprehended as completely as our means of cognition allow.

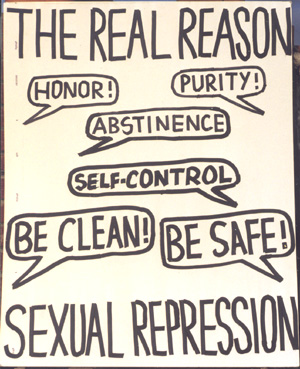

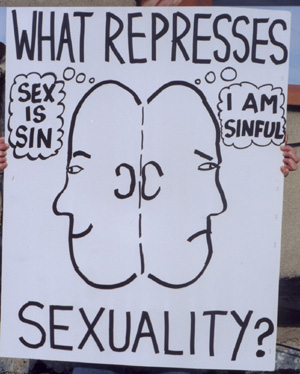

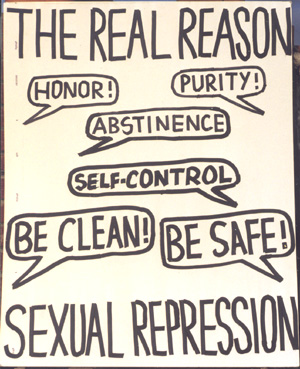

THE SOCIAL FUNCTION OF SEXUAL REPRESSION

Even Lenin noted a peculiar, irrational behavior on the part of the masses before and in the process of a revolt. On the soldiers' revolt in Russia in 1905, he wrote:

"The soldier had a great deal of sympathy for the cause of the peasant; at the mere mention of land, his eyes blazed with passion. Several times military power passed into the hands of the soldiers, but this power was hardly ever used resolutely. The soldiers wavered. A few hours after they had disposed of a hated superior, they released the others, entered into negotiations with the authorities, and then had themselves shot, submitted to the rod, had themselves yoked again."

-Ueber Religion p. 65

Any mystic will explain such behavior on the basis of man's eternal moral nature, which, he would contend, prohibits a rebellion against the divine scheme and the "authority of the state" and its representatives. The vulgar Marxist simply disregards such phenomena, and he would have neither an understanding nor an explanation for them because they are not to be explained from a purely economic point of view. The Freudian conception comes considerably closer to the facts of the case, for it recognizes such behavior as the effect of infantile guilt-feelings toward the father figure. Yet it fails to give us any insight into the' sociological origin and function of this behavior, and for that reason does not lead to a practical solution. It also overlooks the connection between this behavior and the repression and distortion of the sexual life of the broad masses.

To help clarify our approach to the investigation of such irrational mass psychological phenomena, it is necessary to take a cursory glance at the line of questioning of sex economy, which is treated in detail elsewhere.

Sex-economy is a field of research that grew out of the sociology of human sexual life many years ago, through the application of functionalism in this sphere, and has acquired a number of new insights. It proceeds from the following presuppositions:

Marx found social life to be governed by the conditions of economic production and by the class conflict that resulted from these conditions at a- definite point of history. It is only seldom that brute force is resorted to in the domination of the oppressed classes by the owners of the social means of production; its main weapon is its ideological power over the oppressed, for it is this ideology that is the mainstay of the state apparatus. We have already mentioned that for Marx it is the living, productive man, with his psychic and physical disposition, who is the first presupposition of history and of politics. The character structure of active man, the so-called "subjective factor of history" in Marx's sense, remained uninvestigated because Marx was a sociologist and not a psychologist, and because at that time scientific psychology did not exist. Why man had allowed himself to be exploited and morally humiliated, why, in short, he had submitted to slavery for thousands of years, remained unanswered; what had been ascertained was only the economic process of society and the mechanism of economic exploitation.

Just about half a century later, using a special method he called psychoanalysis, Freud discovered the process that governs psychic life. His most important discoveries, which had a devastating and revolutionary effect upon a large number of existing ideas (a fact that garnered him the hate of the world in the beginning), are as follows:

Consciousness is only a small part of the psychic life; it itself is governed by psychic, processes that take place unconsciously and are therefore not accessible to conscious control. Every psychic experience (no matter how meaningless it appears to be), such as a dream, a useless performance, the absurd utterances of the psychically sick and mentally deranged, etc., has a function and a "meaning" and-can be completely understood if one can succeed in tracing its etiology. Thus psychology, which had been steadily deteriorating into a kind of physics of the brain ("brain mythology") or into a theory of a mysterious objective Geist, entered the domain of natural science.

Freud's second great discovery was that even the small child develops a lively sexuality, which has nothing to do with procreation; that, in other words, sexuality and procreation, and sexual and genital, are not the same. The analytic dissection of psychic processes further proved that sexuality, or rather its energy, the libido, which is of the body, is the prime motor of psychic life. Hence, the biologic presuppositions and social conditions of life overlap in the mind.

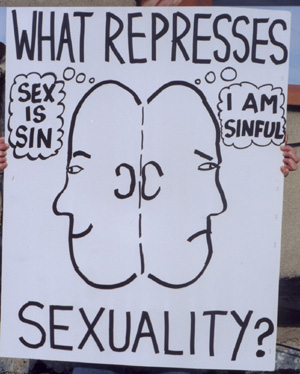

The third great discovery was that childhood sexuality, of which what is most crucial in the child-parent relationship ("the Oedipus complex") is a part, is usually repressed out of fear of punishment for sexual acts and thoughts (basically a "fear of castration"); the child's sexual activity is blocked and extinguished from memory. Thus, while repression of childhood sexuality withdraws it from the influence of consciousness, it does not weaken its force. On the contrary, the repression intensifies it and enables it to manifest itself in various pathological disturbances of the mind. As there is hardly an exception to this rule among "civilized man," Freud could say that he had all of humanity as his patient.

The fourth important discovery in this connection was that, far from being of divine origin, man's moral code was derived from the educational measures used by the parents and parental surrogates in earliest childhood. At bottom, those educational measures opposed to childhood sexuality are most effective. The conflict that originally takes place between the child's desires and the parent's suppression of these desires later becomes the conflict between instinct and morality within the person. In adults the moral code, which itself is unconscious, operates against the comprehension of the laws of sexuality and of unconscious psychic life; it supports sexual repression ("sexual resistance") and accounts for the widespread resistance to the "uncovering" of childhood sexuality.

Through their very existence, each one of these discoveries (we named only those that were most important for our subject) constitutes a severe blow to reactionary moral philosophy and especially to religious metaphysics, both of which uphold eternal moral values, conceive of the world as being under the rulership of an objective "power," and deny childhood sexuality, in addition to confining sexuality to the function of procreation. However, these discoveries could not exercise a significant influence because the psychoanalytic sociology that was based on them retarded most of what they had given in the way of progressive and revolutionary impetus. This is not the place to prove this. Psychoanalytic sociology tried to analyze society as it would analyze an individual, set up an absolute antithesis between the process of civilization and sexual gratification, conceived of destructive instincts as primary biological facts governing human destiny immutably, denied the existence of a matriarchal primeval period, and ended in a crippling skepticism, because it recoiled from the consequences of its own discoveries. Its hostility toward efforts proceeding on the basis of these discoveries goes back many years, and its representatives are unswerving in their opposition to such efforts. All of this has not the slightest effect on our determination to defend Freud's great discoveries against every attack, regardless of origin or source.

Sex-economic sociology's line of questioning, which is based on these discoveries, is not one of the typical attempts to supplement, replace, or confuse Marx with Freud or Freud with Marx. In an earlier passage we mentioned the area in historical materialism where psychoanalysis has to fulfill a scientific function, which social economy is not in a position to accomplish: the comprehension of the structure and dynamics of ideology, not of its historical basis. By incorporating the insights afforded by psychoanalysis, sociology attains a higher standard and is in a much better position to master reality; the nature of man's structure is finally grasped. It is only the narrow-minded politician who will reproach character-analytic structure psychology for not being able to make immediate practical suggestions. And it is only a political loudmouth who will feel called upon to condemn it in total because it is afflicted with all the distortions of a conservative view of life. But it is the genuine sociologist who will reckon psychoanalysis' comprehension of childhood sexuality as a highly significant revolutionary act.

It follows of itself that the science of sex-economic sociology, which builds upon the sociological groundwork of Marx and the psychological groundwork of Freud, is essentially a mass psychological and sex-sociological science at the same time. Having rejected Freud's philosophy of civilization, (In which, despite all its idealism, more truth is found about living life than in all sociologies and some Marxist psychologies taken together) it begins where the clinical psychological line of questioning of psychoanalysis ends.

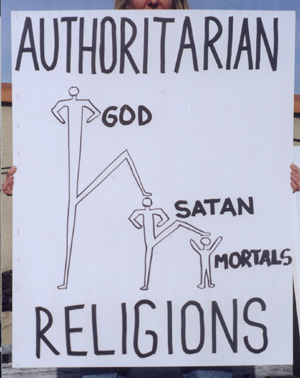

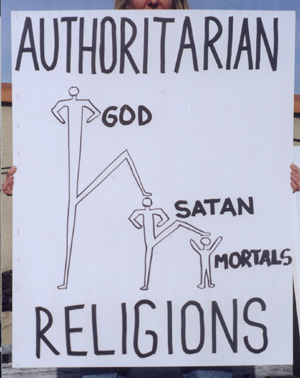

Psychoanalysis discloses the effects and mechanisms of sexual suppression and repression and of their pathological consequences in the individual. Sex-economic sociology goes further and asks: For what sociological reasons is sexuality suppressed by the society and repressed by the individual? The church says it is for the sake of salvation beyond the grave; mystical moral philosophy says that it is a direct result of man's eternal ethical and moral nature; the Freudian philosophy of civilization contends that this takes place in the interest of "culture." One becomes a bit skeptical and asks how is it possible for the masturbation of small children and the sexual intercourse of adolescents to disrupt the building of gas stations and the manufacturing of airplanes. It becomes apparent that it is not cultural activity itself which demands suppression and repression of sexuality, but only the present forms of this activity, and so one is willing to sacrifice these forms if by so doing the terrible wretchedness of children and adolescents could be eliminated. The question, then, is no longer one relating to culture, but one relating to social order. If one studies the history of sexual suppression and the etiology of sexual repression, one finds that it cannot be traced back to the beginnings of cultural development; suppression and repression in other words, are not the presuppositions of cultural development. It was not until relatively late, with the establishment of an authoritarian patriarchy and the beginning of the division of the classes, that suppression of sexuality begins to make its appearance. It is at this stage that sexual interests in general begin to enter the service of a minority's interest in material profit; in the patriarchal marriage and family this state of affairs assumes a solid organizational form. With the restriction and suppression of sexuality, the nature of human feeling changes; a sex-negating religion comes into being and gradually develops its own sexpolitical organization, the church with all its predecessors, the aim of which is nothing other than the eradication of man's sexual desires and consequently of what little happiness there is on earth. There is good reason for all this when seen from the perspective of the now-thriving exploitation of human labor.

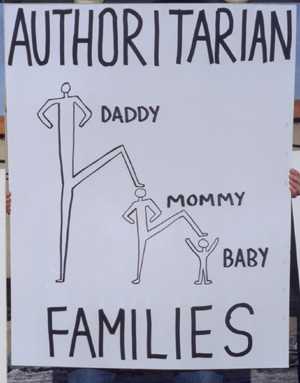

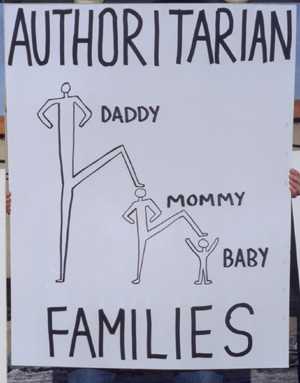

To comprehend the relation between sexual suppression and human exploitation, it is necessary to get an insight into the basic social institution in which the economic and sex-economic situation of patriarchal authoritarian society are interwoven. Without the inclusion of this institution, it is not possible to understand the sexual economy and the ideological process of a patriarchal society. The psychoanalysis of men and women of all ages, all countries, and every social class shows that: The interlacing of the socio. economic structure with the sexual structure of society and the structural reproduction of society take place in the first four or five years and in the authoritarian family. The church only continues this function later. Thus, the authoritarian state gains an enormous interest in the authoritarian family: It becomes the factory in which the state's structure and ideology are molded.

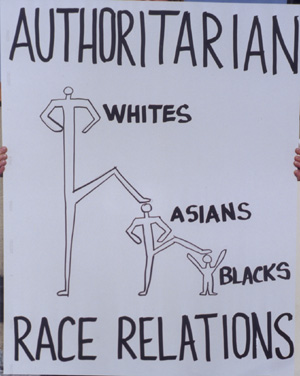

We have found the social institution in which the sexual and the economic interests of the authoritarian system converge. Now we have to ask how this convergence takes place and how it operates. Needless to say, the analysis of the typical character structure of reactionary man (the worker included) can yield an answer only if one is at all conscious of the necessity of posing such a question. The moral inhibition of the child's natural sexuality, the last stage of which is the severe impairment of the child's genital sexuality, makes the child afraid, shy, fearful of authority, obedient, 'good," and "docile" in the authoritarian sense of the words. It has a crippling effect on man's rebellious forces because every vital life-impulse is now burdened with severe fear; and since sex is a forbidden subject, thought in general and man's critical faculty also become inhibited. In short, morality's aim is to produce acquiescent subjects who, despite distress and humiliation, are adjusted to the authoritarian order. Thus, the family is the authoritarian state in miniature, to which the child must learn to adapt himself as a preparation for the general social adjustment required of him later. Man's authoritarian structure-this must be clearly established-is basically produced by the embedding of sexual inhibitions and fear in the living substance of sexual impulses.

We will readily grasp why sex-economy views the family as the most important source for the reproduction of the authoritarian social system when we consider the situation of the average conservative worker's wife. Economically she is just as distressed as a liberated working woman, is subject to the same economic situation, but she votes for the Fascist party; if we further clarify the actual difference between the sexual ideology of the average liberated woman and that of the average reactionary woman, then we recognize the decisive importance of sexual structure. Her anti-sexual, moral inhibitions prevent the conservative woman from gaining a consciousness of her social situation and bind her just as firmly to the church as they make her fear "sexual Bolshevism." Theoretically, the state of affairs is as follows: The vulgar Marxist who thinks in mechanistic terms assumes that discernment of the social situation would have to be especially keen when sexual distress is added to economic distress. If this assumption were true, the majority of adolescents and the majority of women would have to be far more rebellious than the majority of men. Reality reveals an entirely different picture, and the economist is at a complete loss to know how to deal with it. He will find it incomprehensible that the reactionary woman is not even interested in hearing his economic program. The explanation is: The suppression of one's primitive material needs compasses a different result than the suppression of one's sexual needs. The former incites to rebellion, whereas the latter-inasmuch as it causes sexual needs to be repressed, withdraws them from consciousness and anchors itself as a moral defense-prevents rebellion against both forms of suppression. Indeed, the inhibition of rebellion itself is unconscious. In the consciousness of the average nonpolitical man there is not even a trace of it.

The result is conservatism, fear of freedom, in a word, reactionary thinking.

It is not only by means of this process that sexual repression strengthens political reaction and makes the individual in the masses passive and nonpolitical; it creates a secondary force in man's structure-an artificial interest, which actively supports the authoritarian order. When sexuality is prevented from attaining natural gratification, owing to the process of sexual repression, what happens is that it seeks various kinds of substitute gratifications. Thus, for instance, natural aggression is distorted into brutal sadism, which constitutes an essential part of the mass psychological basis of those imperialistic wars that are instigated by a few. To give another instance: From the point of view of mass psychology, the effect of militarism is based essentially on a libidinous mechanism. The sexual effect of a uniform, the erotically provocative effect of rhythmically executed goose-stepping, the exhibitionistic nature of militaristic procedures, have been more practically comprehended by a salesgirl or an average secretary than by our most erudite politicians. On the other hand it is political reaction that consciously exploits these sexual interests. It not only designs flashy uniforms for the men, it puts the recruiting into the hands of attractive women. In conclusion, let us but recall the recruiting posters of war-thirsty powers, which ran something as follows: "Travel to foreign countries-join the Royal Navy!" and the foreign countries were portrayed by exotic women. And why are these posters effective? Because our youth has become sexually starved owing to sexual suppression.

The sexual morality that inhibits the will to freedom, as well as those forces that comply with authoritarian interests, derive their energy from repressed sexuality. Now we have a better comprehension of an essential part of the process of the "repercussion of ideology on the economic basis": sexual inhibition changes the structure of economically suppressed man in such a way that he acts, feels, and thinks contrary to his own material interests.

Thus, mass psychology enables us to substantiate and interpret Lenin's observation. In their officers the soldiers of 1905 unconsciously perceived their childhood fathers (condensed in the conception of God), who denied sensuality and whom one could neither kill nor want to kill, though they shattered one's joy of life. Both their repentance and their irresolution subsequent to the seizure of power were an expression of its opposite, hate transformed into pity, which as such could not be translated into action.

Thus, the practical problem of mass psychology is to actuate the passive majority of the population, which always helps political reaction to achieve victory, and to eliminate those inhibitions that run counter to the development of the will to freedom born of the socio-economic situation. Freed of its bonds and directed into the channels of the freedom movement's rational goals, the psychic energy of the average mass of people excited over a football game or laughing over a cheap musical would no longer be capable of being fettered. The sex-economic investigation that follows is conducted from this point of view.

The Authoritarian Ideology of the Family in the Mass Psychology of Fascism

FUHRER AND MASS STRUCTURE

If, at some future date, the history of social processes would allow the reactionary historian time to indulge in speculations on Germany's past, he would be sure to perceive in Hitler's success in the years between 1928 and 1933 the proof that a great man makes history only inasmuch as he inflames the masses with "his idea." In fact, National Socialist propaganda was built upon this "fuhrer ideology." To the same limited extent to which the propagandists of National Socialism understood the mechanics of their success, they were able to comprehend the historical basis of the National Socialist movement. This is very well illustrated by an article published at that time entitled, "Christianity and National Socialism," written by the National Socialist Wilhelm Stapel. He stated: "For the very reason that National Socialism is an elementary movement, it cannot be gotten at with 'arguments.' Arguments would be effective only if the movement had gained its power by argumentation."

In keeping with this peculiarity the rally speeches of the National Socialists were very conspicuous for their skillfulness in operating upon the emotions of the individuals in t: the masses and of avoiding relevant arguments as much as >~: possible. In various passages in his book Mein Kampf Hitler stresses that true mass psychological tactics dispense with argumentation and keep the masses' attention fixed o n the "great final goal" at all times. What the final goal looked like after the seizure of power can easily be shown by Italian fascism. Similarly, Goring's decrees against the economic organizations of the middle classes, the rebuff to the "second revolution," which was expected by the partisans, the failure to fulfill the promised socialist measures, etc., revealed the reactionary function of fascism. The following view shows just how little Hitler himself understood the mechanism of his success:

"This broadness of outline from which we must never depart, in combination with steady, consistent emphasis, allows our final success to mature. And then, to our amazement, we shall see what tremendous results such perseverance leads to-to results that are almost, beyond our understanding."

~ Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler, translated by Ralph Manheim, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1943, p. 185.

Hitler's success, therefore, could certainly not be explained on the basis of his reactionary role in the history of capitalism, for this role, had it been openly avowed in his propaganda, would have achieved the opposite of that which was intended. The investigation of Hitler's mass psychological effect has to proceed from the presupposition that a fuhrer, or the champion of an idea, can be successful (if not in a historical, then at least in a limited perspective) only if his personal point of view, his ideology, or his program hears a resemblance to the average structure of a broad category of individuals. This leads to the question: To what historical and sociological situation do these mass structures owe their genesis? And so the line of questioning of mass psychology is shifted from the metaphysics of the "fuhrer idea" to the reality of social life. Only when the structure of the fuhrer's personality is in harmony with the structure of broad groups can a "fuhrer" make history, and whether he makes a permanent or only a temporary impact on history depends solely upon whether his program lies in the direction of progressive social processes or whether it stems them. Hence one is on the wrong scent when one attempts to explain Hitler's success solely on the basis of the demagogy of the National Socialists, the "befogging of the masses," their "deception," or to apply the vague, hollow term "Nazi psychosis," as the Communists and other politicians did later. For it is precisely a question of understanding why the masses proved to he accessible to deception, befogging, and a psychotic situation. Without a precise knowledge of what goes on in the masses, the problem cannot be solved. To assert that the Hitler movement was a reactionary movement is not enough. The NSDAP's mass success is inconsistent with this supposed reactionary role, for why would millions upon millions affirm their own suppression? Here is a contradiction that can be explained only by mass psychology-and not by politics or economics.

National Socialism made use of various means in dealing with various classes, and made various promises depending upon the social class it needed at a particular time. In the spring of 1933, for example, it was the revolutionary character of the Nazi movement that was given particular emphasis in Nazi propaganda in an effort to win over the industrial workers, and the first of May was "celebrated," but only after the aristocracy had been appeased in Potsdam. To ascribe the success solely to political swindle, however, would be to become entangled in a contradiction with the basic idea of freedom, and would practically exclude the possibility of a social revolution. What must be answered is: Why do the masses allow themselves to he politically swindled? The masses had every possibility of evaluating the propaganda of the various parties. Why didn't they see that, while promising the workers that the owners of the means of production would be disappropriated, Hitler promised the capitalists that their rights would be protected?

Hitler's personal structure and his life history are of no importance whatever for an understanding of National Socialism. It is interesting, however, that the lower middle-class origin of his ideas coincides in the main with the mass structures, which eagerly accepted these ideas.

As is done in every reactionary movement, Hitler relied upon the various strata of the lower middle class for his support. National Socialism exposes all the contradictions that characterize the mass psychology of the petty bourgeois. Now it is a question of (1) comprehending the contradictions themselves, and (2) getting an insight into their common origin in the conditions of imperialistic production. We will restrict ourselves to questions of sex ideology.

from the Race Theory

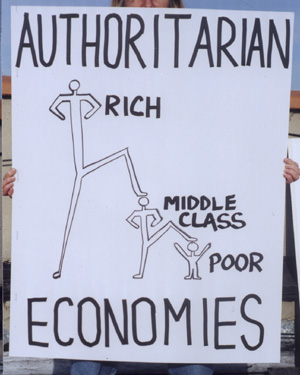

Since sexual suppression has its origin in the economic interest of marriage and the law of inheritance, it begins within the ruling class itself. At first the morality of chastity applies most rigidly to the female members of the ruling class. This is intended to safeguard those possessions that were acquired through the exploitation of the lower classes.

In early capitalism and in the large feudal societies of Asia the ruling class is not yet interested in a sexual suppression of the enslaved classes. It is when the materially suppressed classes begin to organize themselves, begin to fight for socio-political improvements and to raise the cultural level of the broad masses, that sexual-moralistic inhibitions set in. Only then does the ruling caste begin to show an interest in the "morality" of the suppressed classes. Thus, parallel to the rise of the organized working class, a contrary process sets in, namely the ideological assimilation he ruling class.

Their own sexual habits are not relinquished in this process, however, they continue to exist alongside the moralistic ideologies, which, from now on, become more and are entrenched.

from: Some Questions of Sex-Political Practice

As might be expected, the mystical attitude operates as a powerful resistance to the uncovering of unconscious psychic life, especially to repressed genitality. It is significant that mysticism tends to ward off natural genital impulses, especially childhood masturbation, more so than it tends to ward off pregenital infantile impulses. The patient clings to his ascetic, moralistic, and mystical views and sharpens the philosophically unbridgeable antithesis between "the moral element" and "the animal element" in man, i.e., natural sexuality. He defends himself against his genital sexuality with the help of moralistic deprecation. He accuses those around him of not having an understanding for "spiritual values" and of being "crude, vulgar, and materialistic." In short, to one who knows the argumentation of the mystics and fascists in political discussions, and of the characterologists and "scholars" in natural scientific discussions, all this sounds all too familiar. It is one and the same thing. Characteristically, the fear of God and the moralistic defense are immediately strengthened when one succeeds in loosening an element of sexual repression. If one succeeds in getting rid of the childhood fear of masturbation and as a result thereof genitality demands gratification, then intellectual insight and sexual gratification are wont to prevail. To the same extent to which the fear of sexuality or the fear of the old parental sexual prohibition disappears, mystical sentiments also vanish. What has taken place? Prior to this the patient had made use of mysticism to hold his sexual desires in suppression. His ego was too deeply steeped in fear, his own sexuality too deeply estranged, to enable him to master and to regulate the powerful natural forces. On the contrary, the more he resisted his sexuality, the more imperative his desires became. Hence, his moralistic and mystical inhibitions had to be applied more rigidly. In the course of treatment the ego was strengthened and the infantile dependencies on parents and teachers were loosened. The patient recognized the naturalness of genitality and learned to distinguish between what was infantile and no longer usable in the instincts and what was suited to the demands of life. The Christian youth will soon realize that his intensive exhibitionistic and perverse inclinations refer partly to a regression to early infantile forms of sexuality and partly to an inhibition of genital sexuality. He will also realize that his desires for union with a woman are wholly in keeping with his age and his nature, that indeed it is necessary to gratify them. From now on he no longer has need of the support offered by the belief in an all-powerful God, nor does he have need of moralistic inhibition. He becomes master of his own house and learns to regulate his own sexual economy. Character analysis liberates the patient from the infantile and slavish dependency upon the authority of the father and father surrogates. The strengthening of the ego dissolves the infantile attachment to God, which is a continuation of the infantile attachment to the father. These attachments lose their force. If vegetotherapy subsequently enables the patient to take up a satisfying love life, then mysticism loses its last hold. The case of clerics is especially difficult, for a convincing continuation of their profession, whose physical consequences they have felt on their own body, has become impossible. The only course open to many of them is to replace their priesthood with religious research or teaching.

It is only the analyst who does not understand the genital disturbance of his patients who will not be able to confirm these processes in the mystical man. Nor, however, will they be confirmed by the well-known psychoanalyst and pastor who is of the opinion that one "may sink the plummet of psychoanalysis into the unconscious only so far as ethics permit." We want to have as little to do with such "nonpolitical," "objective" science as with that science that not only goes all out in its fight against the revolutionary ~i consequences of sex-economy as "politics," but even advises mothers to fight the erections of small boys by teaching them exercises in holding their breath. In such cases the problem lies in the process that allows the physician's conscience to accept this line of reasoning and to become a pastor, without however rehabilitating him in the eyes of ~ political reaction. He acts very much as the German SPD members of parliament who sang the German national; anthem at the last sitting of parliament enthusiastically and pleadingly, and still ended up in concentration camps as "Socialists."

from: Biosocial Function of Work

THE PROBLEM OF "VOLUNTARY WORK DISCIPLINE"

Work is the basis of man's social existence. This is stressed by every social theory. In this respect, however, the problem is not that work is the basis of human existence. The problem relates to the nature of work: Is it in opposition to or in harmony with the biologic needs of masses of people? Marx's economic theory proved that everything that is produced in the way of economic values comes about through the expenditure of man's living working power, and not through the expenditure of dead material.

Hence, as the sole force that produces values, human working power deserves the greatest interest and care. In a society under the compulsion of market economy and not use economy, it is out of the question to speak of the care and careful treatment of human working power. Just as any other commodity, this working power is bought and used by the owners of the means of production (the state or individual capitalists). The "wage" received by the working man corresponds approximately to the minimum of what he needs to reproduce his working power. Profit economy has no interest in sparing labor power. As a result of the progressive mechanization and economization of work, so much labor power is made superfluous that there is always a ready replacement for expended labor

The Soviet Union abolished private but not state profit economy. Its original intent was to transform the capitalist 'economization" of work into a socialist "economization" of work. It liberated the productive forces of the country shortened working hours in general; in this way it succeeded in getting through the acute economic crisis of 1929-32 without unemployment. There can be no doubt that the Soviet Union's economizing measures, which were partially socialistic in the beginning, enabled it to satisfy the needs of society as a whole. However, the basic problem of a genuine democracy, a work-democracy, is more than just a problem of economy of labor. More than anything else it is a matter of changing the nature of work so that it ceases to be an onerous duty and becomes a gratifying fulfllment of a need.

The character-analytic investigation of the human function of work (an investigation that is by no means finished) offers us a number of clues which make it possible to solve the problem of alienated work in a practical way. Two basic types of human work can be differentiated with satisfying exactness: work that is compulsive and does not give any pleasure and work that is natural and pleasurable.

To comprehend this differentiation, we must first of all free ourselves of several mechanistic "scientific" views of human work. Experimental psychology considers only the question of which methods lend themselves to the greatest possible utilization of the human labor power. When it speaks of the joy of work, it means the joy an independent scientist or artist derives from his accomplishments. Even the psychoanalytic theory of work makes the mistake of solely and always orienting itself on the model of intellectual accomplishments. The examination of work from the point of view of mass psychology correctly proceeds from the relationship of the worker to the product of his work. This relationship has a socio-economic background and relates to the pleasure the worker derives from his work. Work is a basic biologic activity, which, as life in general, rests on pleasurable pulsation.

The pleasure an "independent" researcher derives from his work cannot be set up as the yardstick of work in general. From a social point of view (any other view would have nothing to do with sociology) the work of the twentieth century is altogether ruled by the law of duty and the necessity of subsistence. The work of hundreds of millions of wage earners throughout the world does not afford them he least bit of pleasure or biologic gratification. Essentially' it is based on the pattern of compulsory work. It is characterized by the fact that it is opposed to the worker's biologic need of pleasure. It ensues from duty and conscience, in order not to go to pieces, and is usually done for others The worker has no interest in the product of his work hence, work is onerous and devoid of pleasure. Work that is based on compulsion, regardless of what kind of compulsion, and not on pleasure, is not only nonfulfilling biologically, but not very productive in terms of economy.

The problem is momentous and not very much is known about it. To begin with, let us try to get a general picture. It is clear that mechanistic, biologically unsatisfying work is a product of the widespread mechanistic view of life and the machine civilization. Can the biologic function of work be reconciled with the social function of work. This is possible, but firmly entrenched ideas and institutions must be radically corrected first.

The craftsman of the nineteenth century still had a full relationship to the product of his work. But when, as in a Ford factory, a worker has to perform one and the same manipulation year in and year out, always working on one detail and never the product as a whole, it is out of the question to speak of satisfying work. The specialized and mechanized division of labor, together with the system of paid labor in general, produce the effect that the working man has no relationship to the machine